Wednesday, March 17, 2010

Sunday, March 7, 2010

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

Monday, February 1, 2010

Monday, January 25, 2010

Wk 3: Photosynth and "Citizens as Sensors" by Julie Fair

Powell Stacks Photosynth

In his article, “Citizens as sensors: the world of volunteered geography,” Michael F. Goodchild explores the new and increasingly common phenomenon he terms ‘volunteered geographic information’ or ‘VGI.’ Goodchild defines VGI as “the widespread engagement of large numbers of private citizens, often with little in the way of formal qualifications, in the creation of geographic information, a function that for centuries has been reserved for official agencies” (p.212). The Microsoft Photosynth program used in this week’s exercise constitutes a good example of a source program for the creation of this type of information, and our “photosynths” constitute concrete examples of a form of this type of information, which this week’s assignment has demonstrated can be accomplished by any computer literate member of society, despite lack of formal training. In the remainder of his article, Goodchild points out the numerous faults of this phenomenon of untrained, voluntary information collection but that, non-the-less, it constitutes a “dramatic innovation that will certainly have profound impacts on geographic information systems,…the discipline of geography and its relation to the public” (p.212). His discussion presents both the pros and cons of this type of information and I will now relay some of his arguments as they relate to my own individual “synth” of the book stacks of Powell Library.

Some would probably see my synth of the lower level book stacks on the interior of Powell Library as less than significant as a source of geographic information. However, when one considers that Powell Library is immense enough to have physical maps of its floor plan stationed at each area of book stacks, the idea gains ground. The information contained in this synth, which gives a close range view of the stacks themselves as well as the seating arrangement in that area, could in fact be very useful in a geographical sense. For example, it could be useful to one trying to find a specific location within Powell itself, especially if synths could be created for the entire interior of Powell library. Owing to the advanced state of digital photography and the unique capacities of Photosynth, zoomed images could be created to show specific listing of books (e.g. “A-K”). Also, because Photosynth allows synths to contain geotags, the information contained in my particular synth could be useful to someone unfamiliar with the UCLA area to get an idea about this particular location (405 Hilgard Ave) or about what its like inside “Powell Library,” perhaps for deciding if a user would like to study there based on seating arrangement or other criteria.

My individual synth is a prime example of the several of the ways Goodchild argues that VGI has potential for good. First, this synth could function in filling in what Goodchild terms, “a yawing gap in the availability of digital geographic information” (p.213). Although Goodchild was referring to a lack of street maps for some cities, the concept also makes sense here, where synths like mine can present information on a particular geographic location at a level of detail that is presently totally lacking. Imagine being able to see what the inside of a building looked like without ever setting foot inside it. This example also demonstrates the potential that this type of mapping has for shifting mapping from uniform information gathering to information gathering based on need, which Goodchild notes is a recent objective of the National Spatial Data Infrastructure (p.217). Under the concept of VPI, information at my synth’s level of detail would only be created for those locations where this information was wanted, thereby eliminating waste. This example also touched on the potential of “humans as sensors.” At present the most detailed geographic information is Google Maps Street View, but if large numbers individuals were constantly acting as sensors creating imagery such as that contained in my synth, the limits to what could be viewed remotely could be stretched. We could have the ability to remotely access information about the visuals of the interiors of buildings, a situation that could never be accomplished through current “scientific” means, such as satellite imagery.

My synth can also be viewed in terms of the negative aspects of VGI. An important idea Goodchild points out, is what VGI can mean for the quality and accuracy of information. His article raises issues surrounding such supposedly credible sources as Google, which he points out has had mis-registration problems of up to 40 meters in their imagery (p.219). If information from a source like Google, which places a decent amount of restriction on participation, has problems like these what does that mean for information created by the completely untrained? In the case of my photosynth, I attached it to a geotag for a particular location based completely on my own powers to determine my synth’s location. Photosynth relied completely on my ability to match my synth to the correct location. Goodchild terms this type of information as “asserted geographic information,” which is “asserted by its creator without citation, reference or other authority” (p.220). Goodchild raises the issue of what this kind of information collection could mean for information quality. Another issue Goodchild raises is the motivation behind people volunteering to create these types of information (p.219). This is significant because it has implications for the direction this type of information will take. In the case of my synth for example, why was only this particular area of Powell Library mapped? It is also significant because it can implications for security and privacy. In the case of my synth, privacy issues are in question because of its inclusion of images of two students. Security issues are in question because, in the wrong hands, this imagery could be used in attempts to compromise students’ safety, such as in engineering an attack of some kind. Thus VGI, such as photosynths, has both pros and cons. The issue still seems only minimally investigated and perhaps only time will ultimately tell whether the benefits of VGI outweigh the pitfalls.

Source: Goodchild, Michael F., "Citizens as sensors: the world of volunteered geographers." GeoJournal. 69 (2007) 211-221

Friday, January 15, 2010

Week 2: Exact Replication of Election Results Map, by Julie fair

My Map

My Map

Monday, January 11, 2010

Week 1: Good and Bad Maps & Census 2k, By Julie Fair

I would consider the first map to be a relatively bad map, foremost due to its lack of key map elements and secondarily due to its visually poor layout. In Geog 168, we learned never to turn in a map without several key map elements that allow the viewer to better understand the content of the map. These elements include: a title, an orientation indicator, a scale indicator, a legend, and source notes. This map is lacking all of these elements, making it difficult to understand what information the map is trying to convey. The lack of elements like a title and legend means that the various different colors have little meaning to the viewer. Thus, the map is not effective in conveying information to the viewer, even if it is based on good data. I would also consider this a bad map due to its unrefined layout, which exhibits unbalanced empty space and inset boxes that are too high up in the visual hierarchy of the map. The empty space of this map appears to occur disproportionately at the top of the map, a space that could be filled with important information, like a title. Also, in the absence of map elements that should occur higher up on the visual hierarchy of the map, the boxes around the insets make them unduly noticeable.

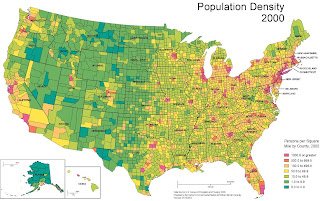

Good Map

Source: goldendome.org/Brahmasthan/index.htm

I would consider the second map to be a relatively good map because it contains all of the map elements described above, aside from an orientation indicator. This inclusion of such elements makes this map much more understandable and therefore, more useful to the viewer. Unlike the first map, this map includes a title which allows the viewer to have a first overall idea of what information the map is trying to convey. The inclusion of a legend is also highly significant, as it informs of the units used in the classification (persons per square mile by county) and what colors represent the highs and lows of classification so the viewer is able to orient itself, unlike in the other map. The inclusion of source information and not one, but three, well placed scale indicators also make this map more useful to the viewer. Although, this map lacks an orientation indicator, the map is fairly understandable due to its familiar subject area (the whole of the U.S.), which a decent amount of people would know is pointing north in this map. Also, the layout of this map is superior to the first map, with empty space being more minimal and more balanced by the inclusion of other map elements, and with the insets being less noticeable, and therefore in a more proper place in the visual hierarchy.

Census 2000 Maps